Blurred Line: Between Fiction & Memoir

I write nonfiction, mostly. Sometimes, I write fiction. I am gay, more than mostly, but I am married to a woman with whom I have two children. I fell in love last year, or I let a manipulative, emotionally abusive man convince me I would never do better so why not settle for what he gave me. I write nonfiction, mostly. Sometimes I write fiction. I am all of these things, and I am none of these things. And I am not alone in thinking that a line exists between fact and fiction (see James Frey, Greg Mortenson, Margaret Jones, et al.), and I’m not even alone in thinking that this line separating fact and fiction might be a bit, well, blurry.

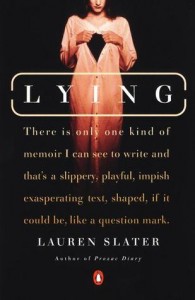

Lauren Slater, in her memoir Lying, argues that your perception of your life is the facts of your life, regardless of whether or not your perception is, well, true.

Publisher’s Weekly, in its review of Lying, might say it best:

If fact is shaded with metaphor, does it become fiction? In a memoir that raises that question, the author of Prozac Diary and Welcome to My Country narrates a life marked by a disease she may or may not actually have. “I have epilepsy,” she writes in the first chapter. “Or I feel I have epilepsy. Or I wish I had epilepsy, so I could find a way of explaining the dirty, spastic glittering place I had in my mother’s heart.” But was it epilepsy, or depression, or bipolar disorder, or Munchausen syndrome, or none of the above? And did Slater really undergo a corpus callostomy operation separating her right and left brain? Questions of authenticity aside, at its core this memoir touchingly describes the coming of age of a young girl who relies on illness to gain the attention of her narcissistic mother and ineffectual father, and who must find a way to navigate her parents’ often vicious marriage and her own troubled adolescence … In her afterword, the author explains that for personal and philosophical reasons, she had no choice but to transcribe her life in “a slippery, playful, impish, exasperating text, shaped, if it could be, like a question mark.”

True story: I enjoy Lauren Slater’s books. Another true story: I dated a man earlier this year who not only hates Lauren Slater’s book, but is not shy in admitting that he might hate her, too. Slater is revered and reviled. She is both. Or maybe she is neither thing. Both opinions are true, though.

True story: I enjoy Lauren Slater’s books. Another true story: I dated a man earlier this year who not only hates Lauren Slater’s book, but is not shy in admitting that he might hate her, too. Slater is revered and reviled. She is both. Or maybe she is neither thing. Both opinions are true, though.

Memory is tricky, especially for a mostly nonfiction writer. I’ve written a book, a memoir (yes I know I’m fairly young to have written a memoir, but I’ve written a memoir), and I opted against using quotation marks. While some of the dialogue I know is verbatim what was said (he and I had a tendency to record things: conversations, concerts, readings, sex), some of the dialogue I’ve recreated, using text messages and letters and my slippery often infallible memory to fill in gaps.

If asked to point out what is fabricated (an ugly word, but I have no other word to use) versus what is transcribed (another ugly word), I’d be hard-pressed to tell you (OK, not true; I know exactly which parts I’ve recreated from memory). And probably, if you ask him, he’d tell you a different story, though he and I lived the same story.

An editor with whom I work frequently and I have been talking about the line between fact and fiction. He also writes nonfiction, mostly. And he writes fiction. And he is contemplating how to marry the two. He and I haven’t landed on a useful solution, but I hope we do, because I’d like a word for it (friction is a good word, but perhaps not appropriate; fictive might work, but that leaves out the nonfictional aspects).

As a graduate student earning my MFA, I enrolled as a fiction writer, and spent a year studying and writing fiction for school, while, during the day, I worked as a reporter, which is clearly not a field in which fiction is wanted let alone celebrated. One afternoon, while meeting with my thesis advisor to begin talking about a story collection I would conceivably, well, conceive, he suggested I take a nonfiction class. Since I traded in nonfiction during the day, maybe something in school would translate. So I took a nonfiction class. With him. And I loved this nonfiction class. Not just because of him. And I quickly learned that all of the elements of strong fiction (character development, dialogue, scene) are elements of strong nonfiction.

So I switched.

Midstream in my program, I switched from fiction to nonfiction, and I based my thesis on work I did for the newspaper, chronicling the first year in the life of a middle school, which was the first new school opened in Marblehead, Massachusetts in some 70 years. The principal gave me full access (well, mostly full access), and I talked to parents and students and school committee members and faculty. Telling the story of this school meant telling the stories of the people inside the school. And telling the story of this school meant stepping away as a just-the-facts-ma’am reporter and lurk in the details.

Am I wandering, here? I might be.

Is there a place for fictional nonfiction? Clearly, we’ve learned that if you market yourself as a nonfiction writer or a memoirist and someone uncovers discrepancies or outright lies in your book, well, good luck with that second book. And I cannot think of another memoirist like Slater who has successfully (my opinion) walked that fine line between fact and fiction, but does so by indicating quite clearly that she is walking this line, and that some of what she’s written is absolutely true, and some of what she’s written is absolutely not true, and she’s not telling you which is which because, at the end of the book, does it matter?

Does knowing what she’s invented change your reading of her memoir? I don’t think so. Or I hope not, because the project on which I’m spending time lately involves children, one of whom can say one word: da-da – so I have to project and I have to interpret and I have to expect that someone, some day, might say, how can any of this be true.

And I will answer: Because I say it’s true.

And that, in this case, will have to do.

[…] more: http://www.spectermagazine.com/content/blog/blurred-line LD_AddCustomAttr("AdOpt", "1"); LD_AddCustomAttr("Origin", "other"); […]

I struggled with Lying mostly because lies are so tricky, or, rather, my relationship with liars is tricky. I tend not to trust much of anything liars say. So, while I liked the way Slater blurred the lines, once I got what she was doing I didn’t trust anything she said. Then I wanted to toss the book out the window. An unreliable narrator in nonfiction is tricky and I suppose my strong of a response to her book shows the many ways she succeeded.

@writersgrind interesting. personally, I like the idea of blurring fiction and memoir. but then, is it still a memoir? is the unreliability further enhanced because of the label? if the story is good, I’m not sure if I care about the narrator’s reliability, no more than one in a novel. but this is @Avesdad’s show. let’s see what he has to say.