Clean-Up On “The Help” by Kathryn Stockett

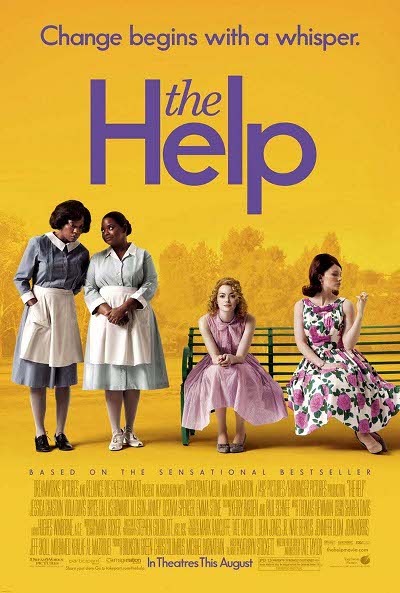

I had a very different post written in my head about Kathryn Stockett’s unintentional big gooey mess of a book The Help. I intended on writing about the messy way she shifts points of view, her sloppy use of dialect; how she blurred the lines of fiction by basing many characters on people from her real life and ending up getting sued by her brother’s housekeeper. But this weekend I saw a screening of the movie and started editing.

I had a very different post written in my head about Kathryn Stockett’s unintentional big gooey mess of a book The Help. I intended on writing about the messy way she shifts points of view, her sloppy use of dialect; how she blurred the lines of fiction by basing many characters on people from her real life and ending up getting sued by her brother’s housekeeper. But this weekend I saw a screening of the movie and started editing.

After reading the novel The Help I had issues with the way Stockett appropriated the stories and took on the voices of the African American women she characterized. I wrote about the mess Stockett creates in a blog post this March, “The Help: Nonfiction Problems in a Fictional Work.” More recently I twittered upon Onyx M’s blog @criticofthehelp, which illuminates even more problems with the novel. So going into the movie I was prepared to hate it. Somehow, I was surprised. Problems still exist in the film version of this story but the filmmakers remedied a few of Stockett gaffs and did manage to capture some of the complexities of these cross-cultural relationships.

One of the major problems from the book remains in the movie: white people are telling an African American story. The movie is based on Stockett’s book and was written and directed by Stockett’s childhood friend Tate Taylor. So even though the movie starts with an Aibileen voice over, even though Aibileen narrates the film, Emma Stone has top billing and like in the book, this is Skeeter (or Stockett’s) story of the help. The white savior problem remains as Skeeter convinces Aibileen to help her tell their story, launch her career and save her from a life as a domestic.

and directed by Stockett’s childhood friend Tate Taylor. So even though the movie starts with an Aibileen voice over, even though Aibileen narrates the film, Emma Stone has top billing and like in the book, this is Skeeter (or Stockett’s) story of the help. The white savior problem remains as Skeeter convinces Aibileen to help her tell their story, launch her career and save her from a life as a domestic.

Stockett’s use of dialect in the book is extremely uncomfortable to read on the page but it sounds a little better onscreen coming from Viola Davis as Aibileen Clark and Octavia Spencer as Minnie Jackson. There are still awkward lines, in particular the scenes with Cicily Tyson as Constantine (whose teeth they made so bad I had to look away) and Aibileen’s, “You is kind. You is smart. You is important,” simply doesn’t work over and over again.

The Black men in this movie (I think there were two speaking parts for black men in the whole thing) mirror the men in the book. Black men are largely absent and abusive in both.

The southern white women are all awful in pretty much the same ways, and except for Skeeter, they follow Hilly Holbrook’s lead as well-meaning racists doing what they can for the starving children in Africa. Unfortunately, any depth of character developed in the Junior League ladies in the book is lost in the screen adaptation. Poor Celia Foote does get a nice make-over in the movie though so rather than being the white-trash alcoholic she is in the book, she is just white-trash which makes her much more palatable. Outstanding performances by the mothers (Allison Janey as Skeeter’s mom and Sissy Spacek as Hilly’s mom) make those two characters most entertaining.

Stockett’s Civil Rights Era flaws are corrected by Hollywood and the use of powerful historical footage of Medgar Evers heightens the racial tension of the time in ways the book never does.

The section of the book about Constantine’s daughter coming back and passing as white is entirely missing from the film.

But in the end, as Skeeter takes off for New York to pursue her dreams as a writer, she never questions if it was her place to tell these stories at all. Aibileen and Minny let her know she has nothing for her in Jackson and she should get out. But what remains for Aibileen and Minny in Jackson? What will happen to Aibileen after she is fired for stealing? She walks away narrating that she will be a writer but how is this possible when another domestic found guilty of theft earlier in the film, ends up in jail.

So, the book is a big, gooey mess of appropriation that blurs the lines of fiction and nonfiction and makes light of historically devastating times. The film successfully avoids a few of the author’s pitfalls but it is, in the end, a comedy. So while the mostly white audience I viewed the movie with both laughed and cried, I felt uncomfortable doing either. It was just too big of a mess for me.

Very interesting and definitely a legit argument/feeling. I haven’t read the book or seen the movie yet, but this makes me want to do so more.

I forgot to mention the chicken! Apparently fried chicken is all the maids cooked. Oh, and it’s a good thing Celia learned how to cook in the movie so Minnie had the strength to leave her abusive husband.