“undun vs. If I Was A Poor Black Kid” by Danielle Scruggs

“They told me that the ends/won’t justify the means/ and they told me at the end/they won’t justify the dreams that I’ve had since a child/maybe I’ll throw in the towel/make my, make my, make my departure from the world.”

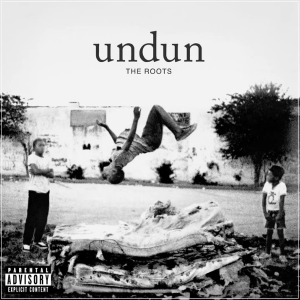

So goes the haunting chorus to “Make My”, a melancholy, organ-tinged song from The Roots’ 13th album, undun. Heavily influenced by blues, jazz, and funk—the underpinnings of hip-hop—the legendary Philly crew’s concept record traces backwards from the untimely death of the fictional Redford Stephens to the circumstances that led to it.

I’ve been listening to undun almost daily for about three weeks. It was around week two that I willed myself to Forbes’ now infamous “If I Was [sic] A Poor Black Kid”, a breathtakingly paternalistic article written by business technology specialist Gene Marks. (Google it, I refuse to contribute to any more of his web traffic.)

[editor’s note: link inserted by Specter Magazine–not to contribute to any more of his web traffic, FYI]

I purposely try to avoid online hoopla and controversy, but given that Forbes pretty much blew up the Internet when they published this article, I had to see for myself why.

Plenty of people have already dissected the ways in which Marks’ proposal for solving the wealth and opportunity gap in this country is problematic so I won’t get into those finer points.

However, what stood out to me most was how Marks completely disregards the actual lives of black people living in poverty and simply reduces them to a nameless, faceless entity: Poor Black Kids. Marks writes as though he is talking about chess pieces, and not individuals with unique sets of circumstances; different hearts and different minds.

And while Stephens is a fictional character, his is a story that, unfortunately, plays out over and over again not just in Philadelphia, the Roots’ hometown, but in Chicago, Baltimore, Oakland, Houston, New Orleans, Bed-Stuy and other American cities.

undun is the story of several people combined into one character, men and women who have little options, little resources, and live in places that many people are too happy to neglect until it suits their agendas.

undun illustrates what happens when people who choose—or, perhaps more accurately, are forced onto—-a path that leads to chaos, destruction, and death, be it spiritual or physical. I’m sad to report that Google Scholar and SparkNotes are not enough to keep people off this path to keep them from going “from a man to memory”, as Black Thought laments on “Sleep” over a spare, percussive beat.

undun illustrates what happens when people who choose—or, perhaps more accurately, are forced onto—-a path that leads to chaos, destruction, and death, be it spiritual or physical. I’m sad to report that Google Scholar and SparkNotes are not enough to keep people off this path to keep them from going “from a man to memory”, as Black Thought laments on “Sleep” over a spare, percussive beat.

It’s a story that some say has been told too many times, that it’s not fresh, it’s been done before.

To that I say, “So what?” It’s a story that needs to be told as many times as it needs to be told, especially with articles like “If I Was A Poor Black Kid” floating around, arguing that people are only living in poverty because they didn’t work hard enough and that we don’t really need to question those circumstances beyond that.

And what makes undun different is this is a story of the true costs of what happens to people with few options and opportunities. It is a story told with little bravado and braggadocio. The one exception is “Stomp”, a hard-rock song driven by electric guitar and stabbing piano keys, where Greg Porn declares at one point, “I’m an evil genius at this dumb shit, I’ma keep it one hundred.”

But for the most part, undun is a story filled with sadness and regret. Grief for lives wasted, through circumstances beyond their control if we are honest with ourselves and how this country actually works. “…It seems like if you scream there’s no one there to hear the sound and it may feel like there’s no one there that cares if you drown…” Dice Raw sings on “Lighthouse”, using a drowning man as a metaphor for being left behind by anyone or anything that you thought would save you—family, lovers, friends, teachers, government, a higher power…take your pick.

Far more effectively, and with a great deal more subtlety and sensitivity than Gene Marks, Ahmir, Tariq, Kirk, Frank, Kamal and Mark have humanized and personalized poverty in inner cities across America. And they have also given us a powerful, timely reminder: We need to tell our own stories.

Once we acquiesce our stories to others, we cease to exist. We become caricatures, faceless entities upon which others can project their own fears and biases, instead of flesh-and-blood human beings with rich inner lives that can’t be explained away so easily.

Yes and I agree totally with this article, it is easy for him and others in his position to speak and say those kinds of things but lets do some research and lets give the money and companies to the poeple who truly established them (slavery) lets take that money that was made from that and give it to the people who actually put in the work and I bet you he, them, they would be singing a very different song. And then speaking on song lets take the money from the rock n roll record companies, the blues and r & b record companies and give it to the families of the people who wrote the songs and composed the music but hey that is a different story……