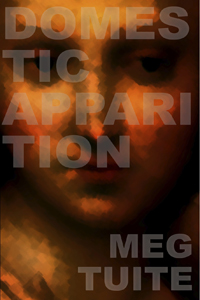

“Domestic Apparition” by Meg Tuite reviewed by Agnes Morton

In her debut novel, Domestic Apparition, which is rather a story collection than a traditionally-plotted novel, Meg Tuite gives us a wonderful tableau of familiar characters: just as if all of it were about our friends, family, colleagues, neighbours, about people we know or knew quite well, even about ourselves… But at the same time these figures seem to be heroes of fairy tales, some details are so fantastic, they could fairly be only well-figured-out parts of thousand-times-told family legends… in the ‘years of fluffy pastel sweaters’ and well beyond. Americana? Surely… but in each and every corner of the world we would be able to find the equivalents… what Meg Tuite is talking about is valid everywhere.

Indeed, we can read about corpse-like, cruel teachers of Catholic schools (evil nuns with men’s names, one of them asking advice from a stuffed raindeer ‘named after one of the most sadistic popes in history: Pope Steven VI’) in the early sixties when ‘abuse was not only condoned, but expected at any and all levels’; sisters smoking a whole nickel bag of pot together at the attic, ignoring their mom yelling at them; the same sisters setting traps for one another; shocking their parents in many ways (for example by telling them proudly about being a lesbian, by stealing credit cards or by making their small cousin drink a glass of Jagermaister).

The girls’ dad (the ‘leader of men’) had a ‘purposefulness of a dog that has come to the end of its chain, but does not agree’ and held the knife ‘forcefully and with authority’ just to show the right way how to use it (because women, the absolutely useless, have to be taught). The child genius brother, Nathan, composed an opera about fish at the age of ten by sitting at the piano and hitting random notes. He worked out a rating system for the commercials between the TV programs (the rating criteria being artistic individuality, humor, acting ability, engaging dialogue and jingle retention). He put together a time capsule with his sisters for future archaeologists – with ‘important specimen of our culture’ (like a lucky rabbit foot). He became a school legend.

We are told about Family Conference sessions where ‘dad’ recites ‘various idiocies of his children and wife’, with family members calling each other bastard and psycho bitch. About adults ‘holding a sunken continent of memories inside.’ About discarded lives, ‘tales of lost loves and exotic places they were going to visit, but never did.’ About irretrievable dreams. About housewives terrorized into a breath of themselves, sucking in abuse and commandments. About an aunt who found the only way for escape in suicide. About the grandmother who ‘has been living, breathing and sucking down the blood of Christ in a lifetime of unparalelled singularity that the clergy can only read about and shamelessly attempt to enact, mouthing their long-winded, incredulous interpretations of the Bible, done up like showgirls in their mawkish vestments’. About silence impossible to talk over. About lost ambitions. About marrying idiots just for the sake of being married. About screaming but only in the privacy of home. About ‘the sinister monotony of the habitual.’ Different but still the same stories of women, ‘just as there are multitudes of roads that lead to the same destination.’

We are told about Family Conference sessions where ‘dad’ recites ‘various idiocies of his children and wife’, with family members calling each other bastard and psycho bitch. About adults ‘holding a sunken continent of memories inside.’ About discarded lives, ‘tales of lost loves and exotic places they were going to visit, but never did.’ About irretrievable dreams. About housewives terrorized into a breath of themselves, sucking in abuse and commandments. About an aunt who found the only way for escape in suicide. About the grandmother who ‘has been living, breathing and sucking down the blood of Christ in a lifetime of unparalelled singularity that the clergy can only read about and shamelessly attempt to enact, mouthing their long-winded, incredulous interpretations of the Bible, done up like showgirls in their mawkish vestments’. About silence impossible to talk over. About lost ambitions. About marrying idiots just for the sake of being married. About screaming but only in the privacy of home. About ‘the sinister monotony of the habitual.’ Different but still the same stories of women, ‘just as there are multitudes of roads that lead to the same destination.’

Women, trash collectors of the past who destroyed their younger selves. Victims of gang rape and champions of seeing farts. Indecent exposures. Distant relationship with money (not having it and looking for it in the wrong places). Girls being kicked out of school and being on anti-anxiety pills, doing some intensive counseling – spending most of their time drunk and high and trying to keep their private hells to themselves. ‘They had that faraway Sylvia Plath look to them – unreachable and not of this planet.’ Shocksters before and after being humiliated. Parents owning a coffee table ‘designed by somebody that many somebodies knew’ – some of them with posters of Klee and Picasso hanging up in their house, some others with THE REAL THING. Campuses with the front doors open – with nothing much to steal, ‘unless you were in the need of a mattress’. Where the most pressing matters are who has cash for beer and where is the next party. ‘Important jobs’ at Holiday Inns, difficult to get in the tough job market – and the cheap suits every day at the very same Holiday Inns, waiting to check out after cheating on their wives. The hell of corporate adverising (or any corporate job), starting with job interviews full of questions like where you see yourself in five years – and then soaking you in, no matter how far away you feel. Slow inner transformations. Lives propelling forward like a soap opera.

History is not left out either. It is always there in the background, for example with a disillusioned hint to the Declaration of Independence, and sentences like ‘Rage was just another person in the room.’

According to a Swedish proverb in a good book the best is between the lines. Meg Tuite’s thin (134-page) but memorable story collection is held together by drama behind the scenes, untold but suggested connections between the rebel and/or lost girls and the soul-slaughtered, cynical, silent women they are maturing into. We just fly from chapter to chapter exploring boldly and fearlessly, in an eloquent and radiant way, how many different versions and shades of dysfunctionality can exist… The narrative is fresh, imaginative, sometimes poetic and witty, with good sense of humour and frequent winks, in a beautiful, smooth flow, giving us a compelling, dynamic read. Perceptive and straight-looking but always compassionate.

All the characters have deep secrets and we are privileged enough to get into the tales of this profound layer of existence, follow these figures into their furtive places… and it takes the breath away.

I am absolutely looking forward to reading other novels from the same author. It would be exciting to see how she can interweave different destinies after an inciting incident, how she can tell us about the step-by-step emotional changes of a protagonist, what other worlds she can lure us into.

Agnes Marton is a Hungarian-born poet, editor (with background in academic and art book publishing), linguist, translator. Regularly works together with visual artists, takes part in exhibitions and art projects in Europe, in the USA and in New Zealand. Performs in five countries. Her book: ‘Sculpture/poésie’ with Mani Bour.

[…] http://www.spectermagazine.com/feature/review/meg-tuite […]